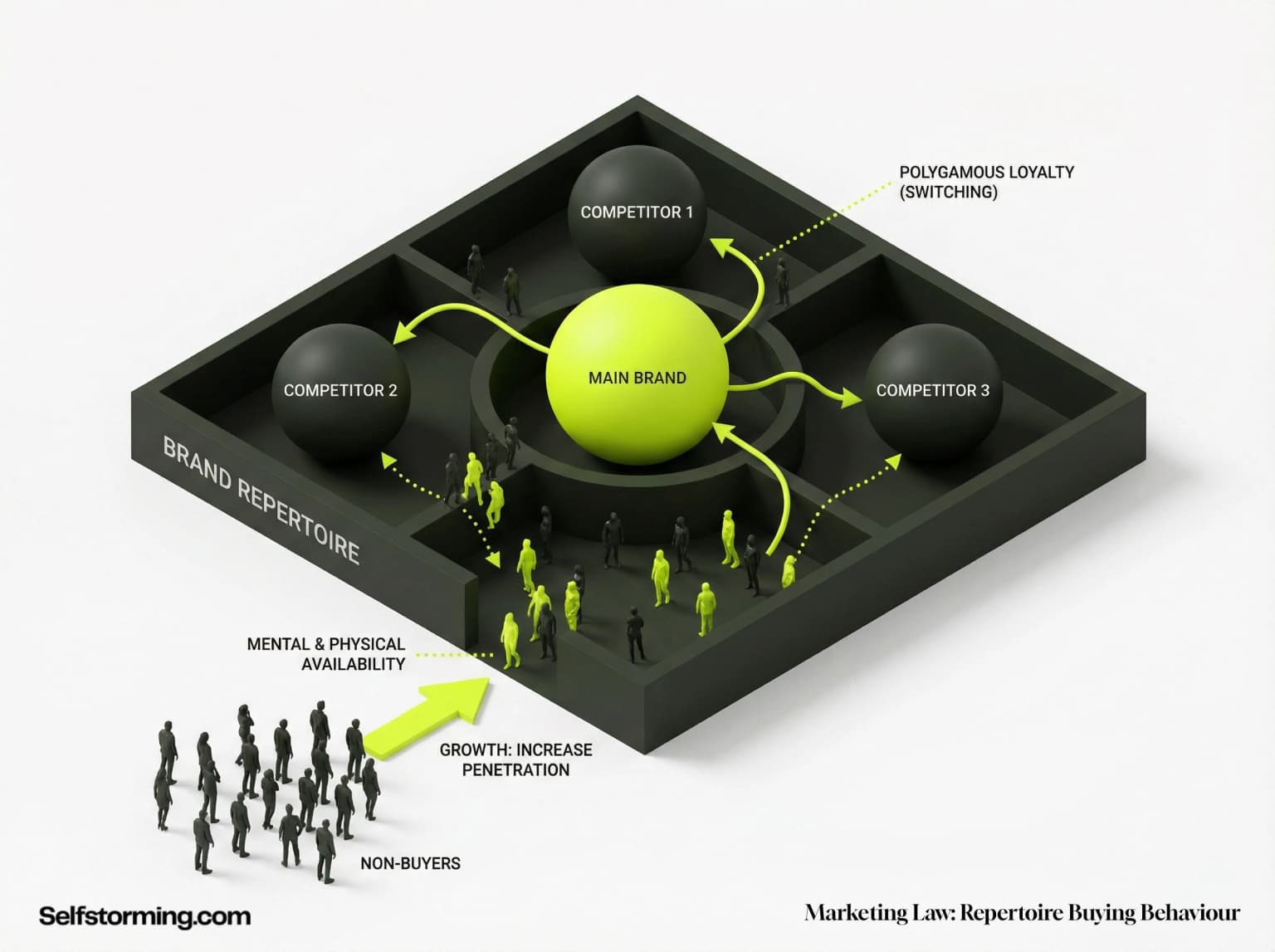

The Law Of Repertoire Buying

Your customers are cheating on you.

I hate to be the one to tell you this, but your loyal customers are cheating on you. Probably right now. They aren't the brand-obsessed disciples your agency's mood board promised. They are busy, distracted humans who keep a mental shortlist of good enough brands and pick whichever one is easiest to grab. You aren't their soulmate; you're just a recurring guest star in their lives. If you want to grow, you need to stop acting like a jealous ex and start understanding the cold, hard math of repertoire buying. It’s not personal; it’s just how brains work.

THE LAW OF REPERTOIRE BUYING

“[PLACEHOLDER] This is not the real definition. We wrote this fake one just to fill the space. Subscribe to see what the law actually says.”

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] Nice try. We see you squinting through the blur. This is filler — the actual insights are subscriber-only. No amount of CSS hacking will reveal the real content.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] Look, we're not mad. Just mildly disappointed. The real breakdown is waiting — you just need to stop trying to cheat and subscribe like everyone else.

Key Takeaways

- [PLACEHOLDER] This is fake takeaway text. The real ones are actually useful. This is just here so the blur looks right.

- [PLACEHOLDER] Another placeholder bullet. The actual insights would help your strategy. This won't.

- [PLACEHOLDER] Still reading? These are literally filler bullets. The paid version has real research-backed points.

- [PLACEHOLDER] Last fake bullet. Subscribe to see what actually matters. Or keep squinting - your call.

Consequences Of Applying The Law

| Aspect | When Applied | When Not Applied |

|---|---|---|

| [PH] | Fake content placeholder. | Still placeholder text. |

| [PH] | More filler text here. | Subscribe to see real data. |

| [PH] | Last fake row here. | Real table has insights. |

Genesis & Scientific Origin

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] This is not the origin story. This is lorem ipsum with attitude. The real history — who discovered this, when, and the research that backs it — is for subscribers only.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] We applaud the effort with inspect element. Truly. But that blur isn't hiding the real text — this IS the placeholder. The actual content lives on our servers, not in your DOM.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] Want to actually impress your CMO with sourced evidence? Yeah, you'll need to pay for that.

“[PLACEHOLDER] This stat is fake. The real one has actual research numbers. Nice try though.”

The Mechanism: How & Why It Works

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] Nice try. This is literally filler text designed to look like content. The actual mechanism breakdown — the stuff that would actually help your career — is for paying members.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] We wrote this placeholder knowing you'd try to read it. So here's a wave: 👋 Hi there, scrappy marketer. We respect the hustle, but this ain't it.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] The real section explains WHY this works psychologically and HOW to apply it. But you're reading gibberish instead. Your choice.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] Scroll up, hit subscribe, and stop wasting time decoding blur. Or don't — the free sample laws are genuinely good too.

Real-World Example:

Major Global Brand

Situation

[PLACEHOLDER] This isn't a real case study. The actual version names the brand and describes what they actually did. You're reading corporate lorem ipsum right now.

Result

[PLACEHOLDER] The real results have actual percentages and revenue numbers. This is just text that kinda looks like content. Subscribe if you want the receipts.

Strategic Implementation Guide

[PLACEHOLDER] Fake Step One

This is placeholder text. The real implementation guide has actual actionable steps. This is just content-shaped filler.

[PLACEHOLDER] Another Fake Step

Still squinting through the blur? These steps won't help you — they're literally made up to fill space.

[PLACEHOLDER] More Filler

The actual guide breaks down exactly how to apply this law. This text just looks like it does.

[PLACEHOLDER] Last Fake Step

Nice try. Subscribe to see the real thing. Or keep reading placeholder text — we won't judge. Much.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does Repertoire Buying mean brand differentiation is useless?

to see the answer

What about Superfans or Brand Evangelists?

to see the answer

Is sole loyalty ever possible?

to see the answer

Does this apply to B2B as well as FMCG?

to see the answer

Should I stop my loyalty program?

to see the answer

Sources & Further Reading

Related Marketing Laws

Double Jeopardy Law

Big brands have more buyers and higher repeat rates. Loyalty follows size, not strategy.

The Growth By Penetration Law

Brands grow mainly by reaching more buyers, not by increasing loyalty.

Light Buyer Law

Most sales come from buyers who purchase infrequently, not heavy users.

The Law Of Profit And Market Share

Larger brands tend to be more profitable due to scale advantages.