The Loyalty Program Law

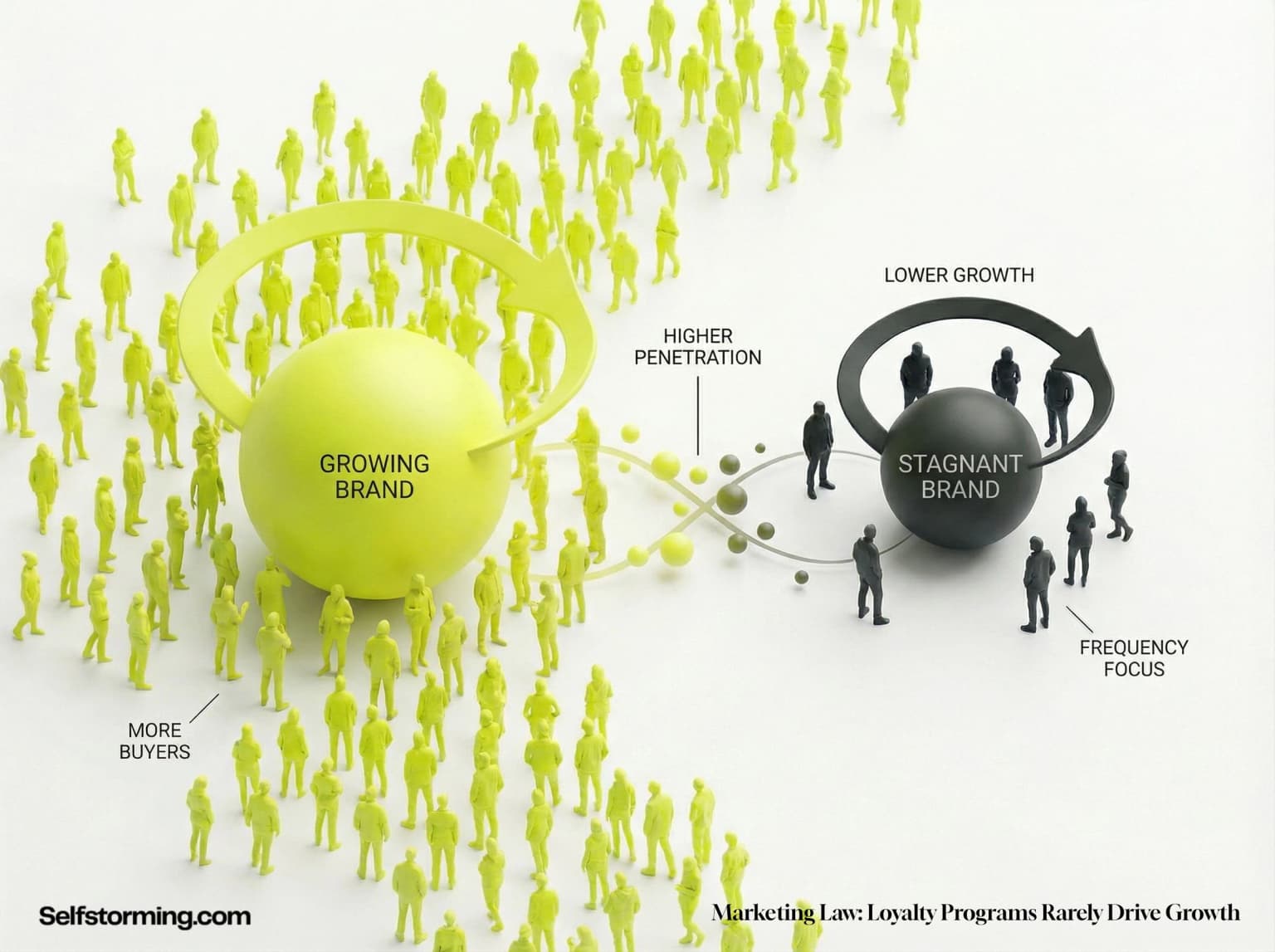

Loyalty cards don't create new fans.

The desire is understandable. You want to feel loved. You want a meaningful relationship with your customers. Newsflash: they don't want a relationship with your detergent brand; they want to buy it and forget you exist. Your loyalty program isn't driving engagement; it's a glorified subsidy for people who were already going to buy from you. You’re essentially paying your best customers to keep doing exactly what they’re already doing, while your competitors are out there actually growing by talking to people who don't know they exist. It’s a statistical suicide note written in points and rewards. Your CRM is a very expensive digital paperweight, and it's time we talked about why.

THE LOYALTY PROGRAM LAW

“[PLACEHOLDER] This is not the real definition. We wrote this fake one just to fill the space. Subscribe to see what the law actually says.”

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] Nice try. We see you squinting through the blur. This is filler — the actual insights are subscriber-only. No amount of CSS hacking will reveal the real content.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] Look, we're not mad. Just mildly disappointed. The real breakdown is waiting — you just need to stop trying to cheat and subscribe like everyone else.

Key Takeaways

- [PLACEHOLDER] This is fake takeaway text. The real ones are actually useful. This is just here so the blur looks right.

- [PLACEHOLDER] Another placeholder bullet. The actual insights would help your strategy. This won't.

- [PLACEHOLDER] Still reading? These are literally filler bullets. The paid version has real research-backed points.

- [PLACEHOLDER] Last fake bullet. Subscribe to see what actually matters. Or keep squinting - your call.

Consequences Of Applying The Law

| Aspect | When Applied | When Not Applied |

|---|---|---|

| [PH] | Fake content placeholder. | Still placeholder text. |

| [PH] | More filler text here. | Subscribe to see real data. |

| [PH] | Last fake row here. | Real table has insights. |

Genesis & Scientific Origin

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] This is not the origin story. This is lorem ipsum with attitude. The real history — who discovered this, when, and the research that backs it — is for subscribers only.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] We applaud the effort with inspect element. Truly. But that blur isn't hiding the real text — this IS the placeholder. The actual content lives on our servers, not in your DOM.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] Want to actually impress your CMO with sourced evidence? Yeah, you'll need to pay for that.

“[PLACEHOLDER] This stat is fake. The real one has actual research numbers. Nice try though.”

The Mechanism: How & Why It Works

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] Nice try. This is literally filler text designed to look like content. The actual mechanism breakdown — the stuff that would actually help your career — is for paying members.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] We wrote this placeholder knowing you'd try to read it. So here's a wave: 👋 Hi there, scrappy marketer. We respect the hustle, but this ain't it.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] The real section explains WHY this works psychologically and HOW to apply it. But you're reading gibberish instead. Your choice.

[PLACEHOLDER TEXT] Scroll up, hit subscribe, and stop wasting time decoding blur. Or don't — the free sample laws are genuinely good too.

Real-World Example:

Major Global Brand

Situation

[PLACEHOLDER] This isn't a real case study. The actual version names the brand and describes what they actually did. You're reading corporate lorem ipsum right now.

Result

[PLACEHOLDER] The real results have actual percentages and revenue numbers. This is just text that kinda looks like content. Subscribe if you want the receipts.

Strategic Implementation Guide

[PLACEHOLDER] Fake Step One

This is placeholder text. The real implementation guide has actual actionable steps. This is just content-shaped filler.

[PLACEHOLDER] Another Fake Step

Still squinting through the blur? These steps won't help you — they're literally made up to fill space.

[PLACEHOLDER] More Filler

The actual guide breaks down exactly how to apply this law. This text just looks like it does.

[PLACEHOLDER] Last Fake Step

Nice try. Subscribe to see the real thing. Or keep reading placeholder text — we won't judge. Much.

Frequently Asked Questions

Doesn't it cost 5x more to acquire a new customer than to retain an existing one?

to see the answer

What about Starbucks? Their loyalty app is incredibly successful.

to see the answer

Can loyalty programs work for niche, high-end brands?

to see the answer

If loyalty programs don't drive growth, why does every big brand have one?

to see the answer

Should we just cancel our loyalty program entirely?

to see the answer

Sources & Further Reading

Related Marketing Laws

The Law Of Overclaimed Differentiation

Most brands are less unique than they believe.

The Law Of Over-Optimization

Excessive testing leads to average, forgettable work.

The Brand Purpose Law

Purpose matters more internally than in buying decisions.

The Messaging Law

A slogan is not a strategy.